Female collaborations in the Alport Collection

Despite the predominance of male writing circles elsewhere in this exhibition, the Alport Collection also incorporates some fine examples of collaborations between women, and, more specifically, sisters.

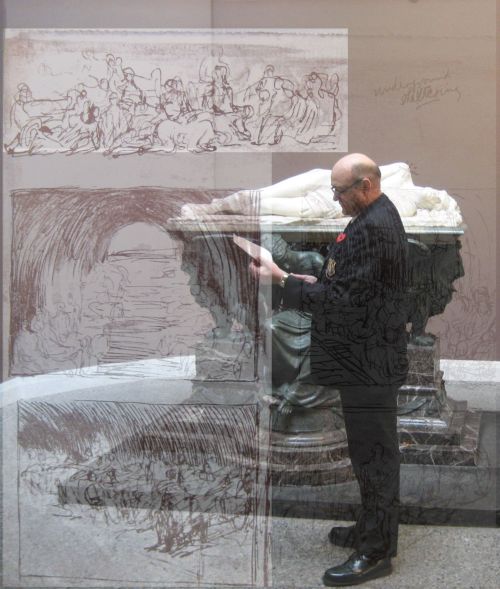

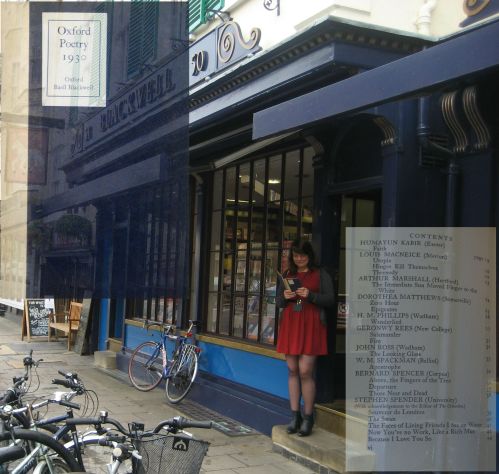

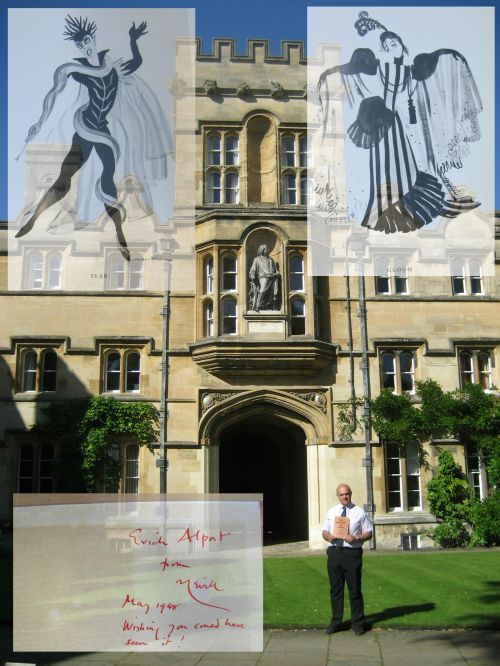

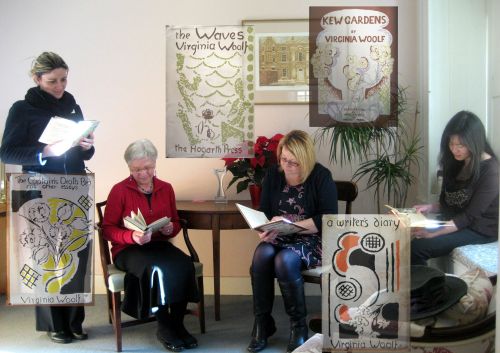

Univ’s Domestic Bursary team looking at some of the Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell collaborations in the Alport Collection.

The Cuala Press

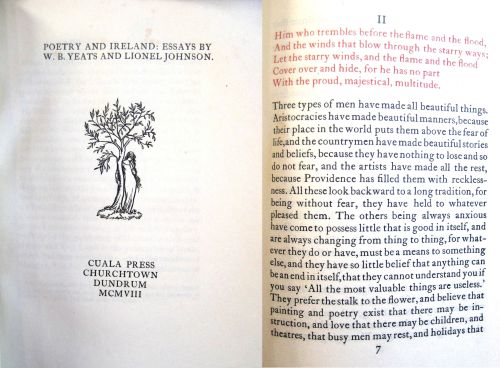

Three types of men have made beautiful things…and the artists have made all the rest because Providence has filled them with recklessness – William Butler Yeats (Poetry and Ireland, 1908)

Lolly (Elizabeth) and Lily (Susan) Yeats started their own business together in 1908. They named their embroidery workshop and printing press Cuala Industries after the Old Irish name for Dundrum where they were based.

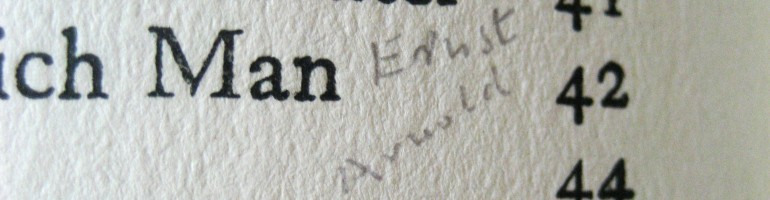

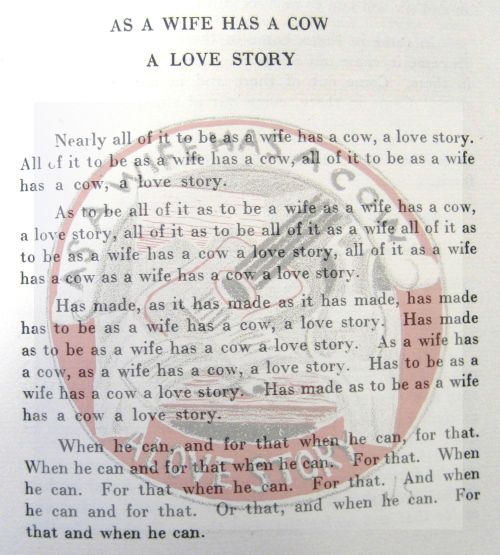

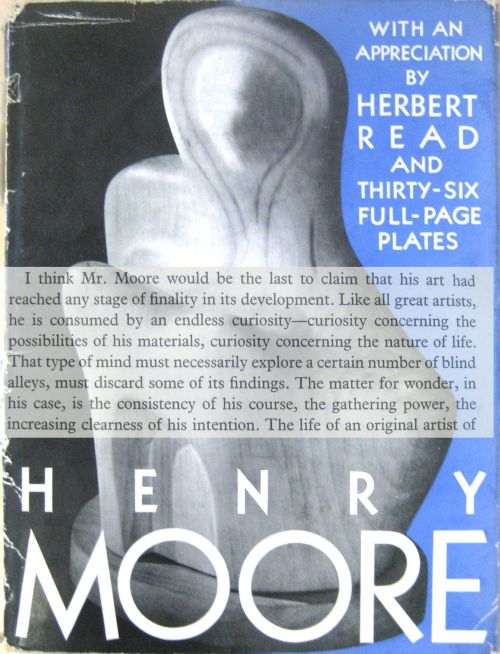

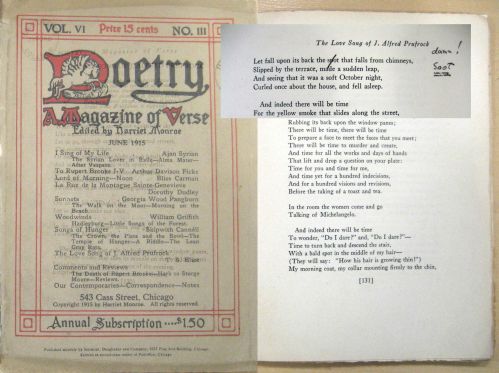

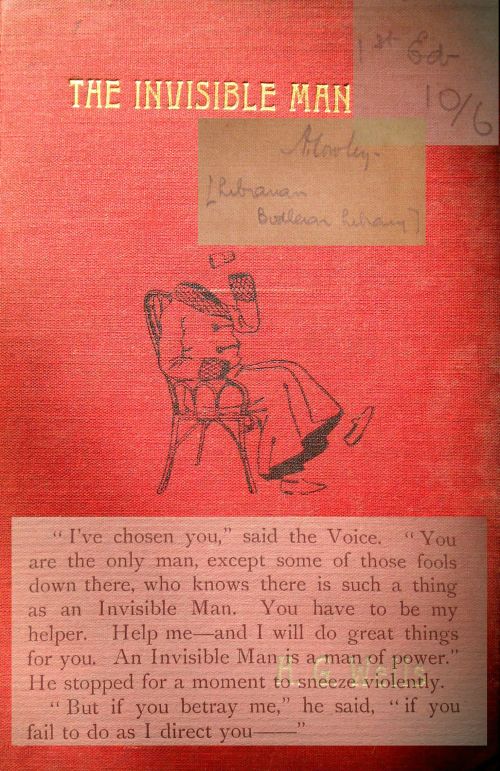

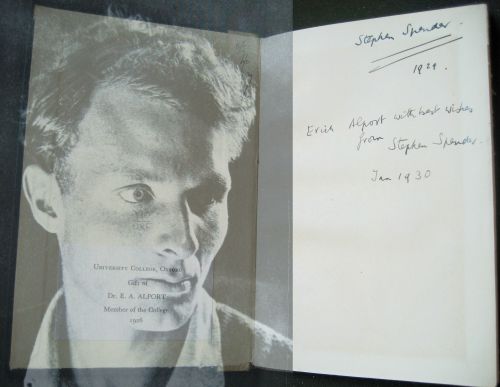

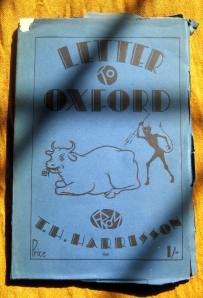

Title page and text from an early production by the Cuala Press, Poetry and Ireland: Essays by W. B. Yeats and Lionel Johnson. Churchtown : Cuala Press. 1908

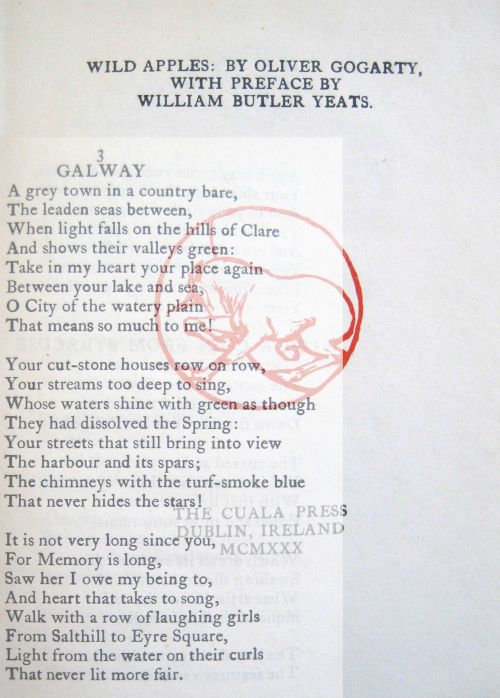

Over the 32 years it ran, the Cuala Press published the work of many contemporary writers, all but two of whom were Irish. This was in contrast to other fine presses of the time which produced beautiful versions of old texts. The Alport Collection offers five of the sixty-six volumes published by Cuala Industries including writing by Lolly and Lily’s brother, William Butler Yeats.

Title page overlaid with the poem “Galway” from Wild Apples by Oliver Gogarty ; with a preface by William Butler Yeats. Dublin : Cuala Press. 1930. Alport’s copy is one of 250 printed.

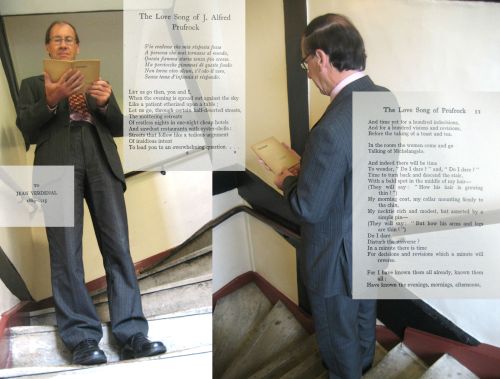

Lolly Yeats’ work at the Cuala Press was influenced by the styling of the Dove Press, established in 1900. The Cuala books exhibit a uniformity of design corresponding to the ideal of 14 point Caslon old style font printed on high quality rag paper made locally, near Dublin. This design is beautiful in its simplicity which allows the text to be read without distraction.

The Stephen Sisters and the Hogarth Press

Brown cliffs with deep green lakes in the hollows, flat blade-like trees that waved from root to tip, round boulders of grey stone, vast crumpled surfaces of a thin crackling texture… – Virginia Woolf (Kew Gardens, 1927)

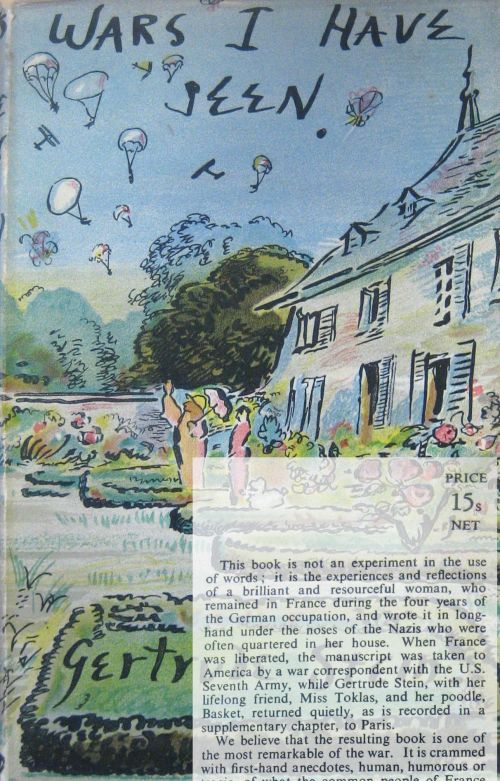

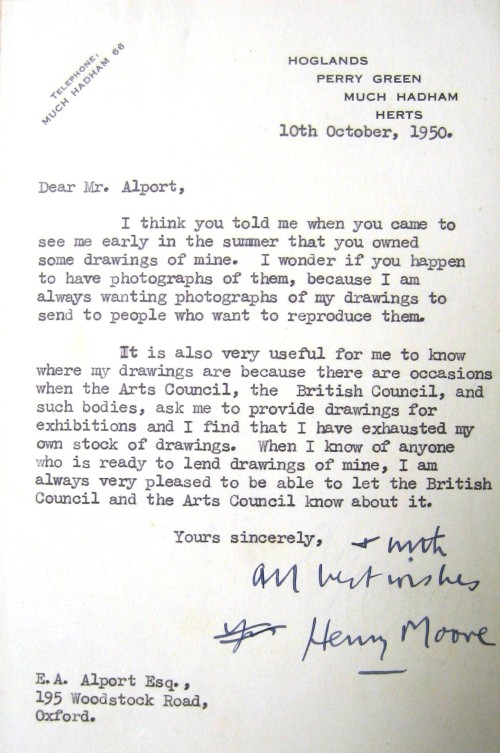

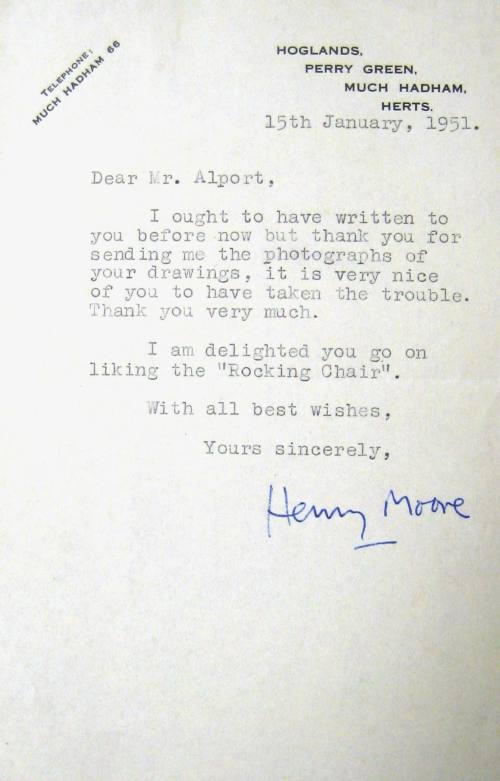

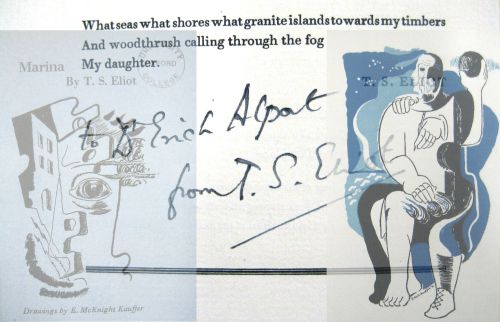

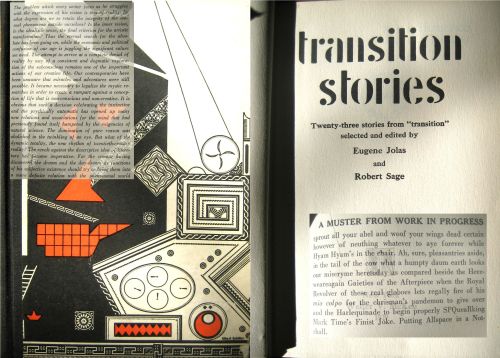

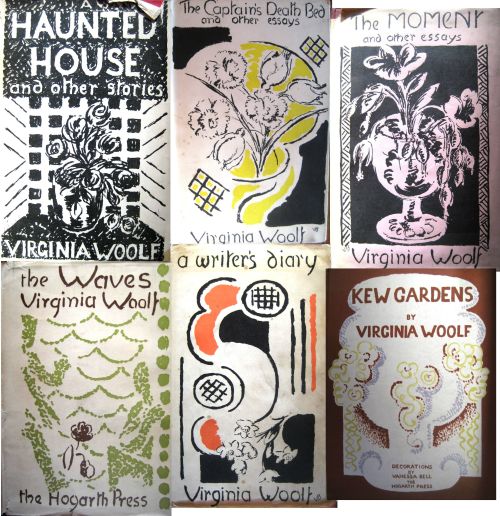

Across the Irish Sea at around the same time, Vanessa and Virginia Stephen were collaborating to produce modernist texts with arresting cover design and illustrations. These sisters are better known to history as the artist, Vanessa Bell and the writer and printer, Virginia Woolf. Many of Woolf’s works were published by the Hogarth Press which she ran with her husband, Leonard. Bell provided the striking cover designs that gave the Press a distinctive house style. She also illustrated some of Woolf’s work more extensively.

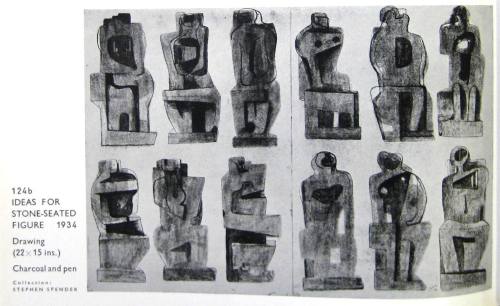

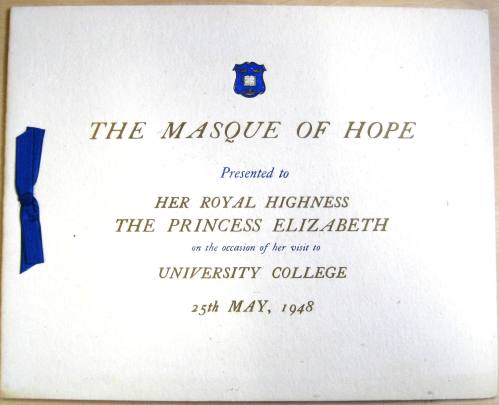

Some of Vanessa Bell’s cover designs for Virginia Woolf’s texts, clockwise from the top left: The Haunted House and Other Stories. London : Hogarth Press. 1943; The Captain’s Death Bed and Other Essays. London : The Hogarth Press. 1950; The Moment and Other Essays. London : The Hogarth Press. 1947; Kew Gardens. London : The Hogarth Press. 1927; A Writer’s Diary. London : The Hogarth Press. 1953; The Waves. London : The Hogarth Press. 1931.

Many artists, writers and critics of the early twentieth century acknowledged the impact on the reader of the design surrounding a text. This put more emphasis on the production of books. Accordingly, it was a period that saw the foundation of many private presses such as the Cuala Press and the Hogarth Press.

Vanessa Bell was greatly influenced by the work of the critic, Roger Fry. His 1927 essay “Book Illustration and a Modern Example” argued that illustrators could provide a visual, critical framework for the reader. Illustration could be marginal notes that did not muddy the waters by introducing words that did not belong to the author.

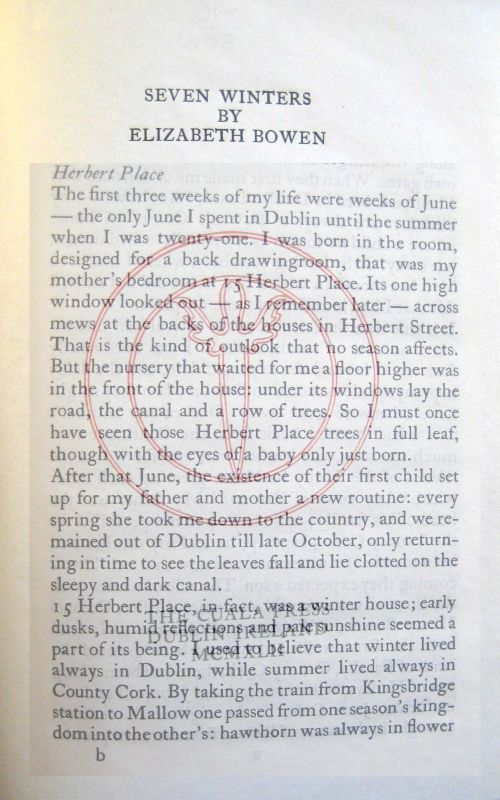

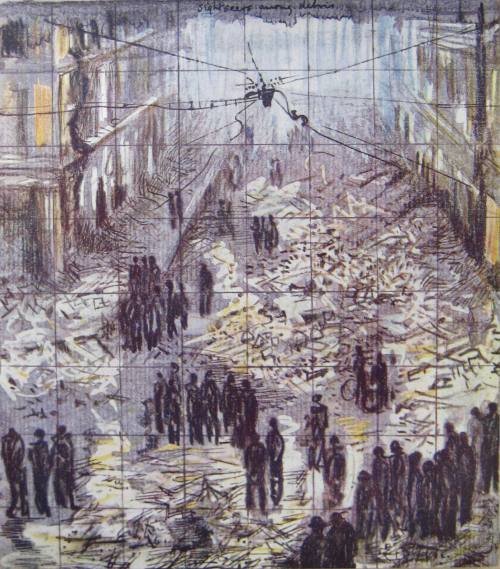

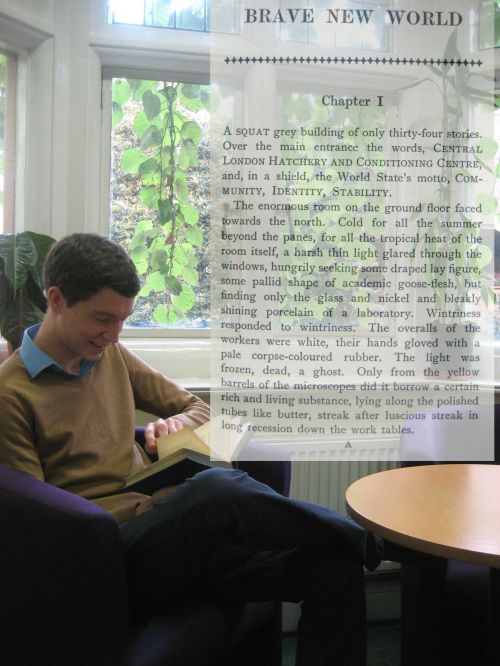

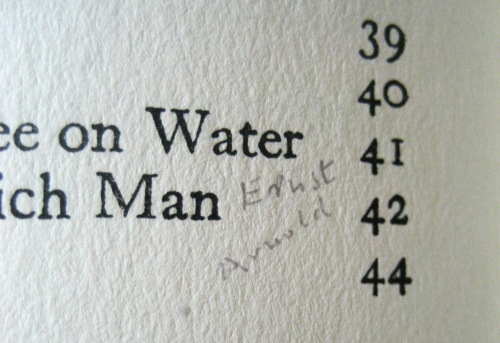

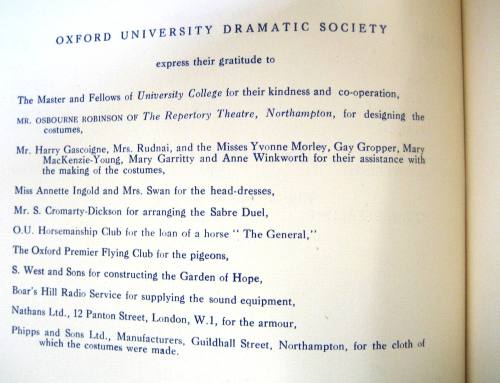

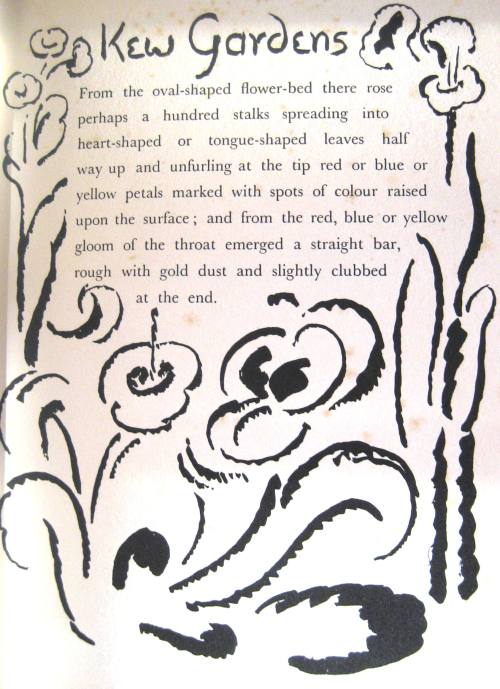

The opening page of Kew Gardens by Virginia Woolf, with illustrations by Vanessa Bell. London : Hogarth Press. 1927. Alport’s copy is number 478 of a limited edition of 500.

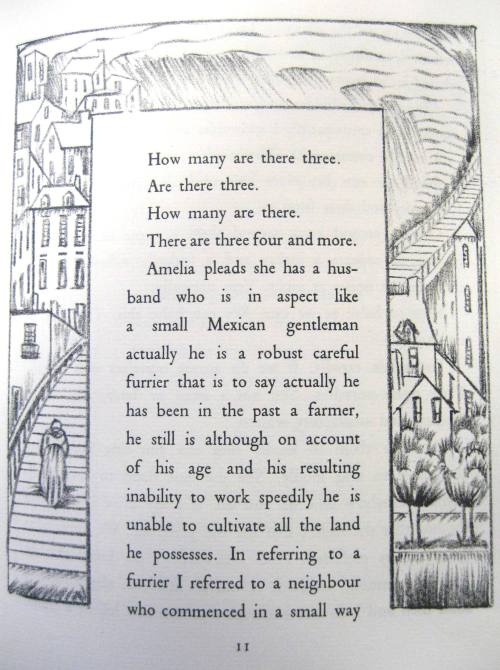

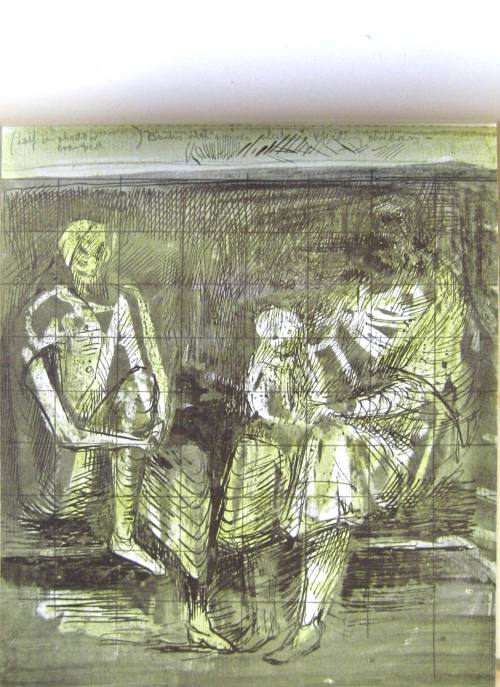

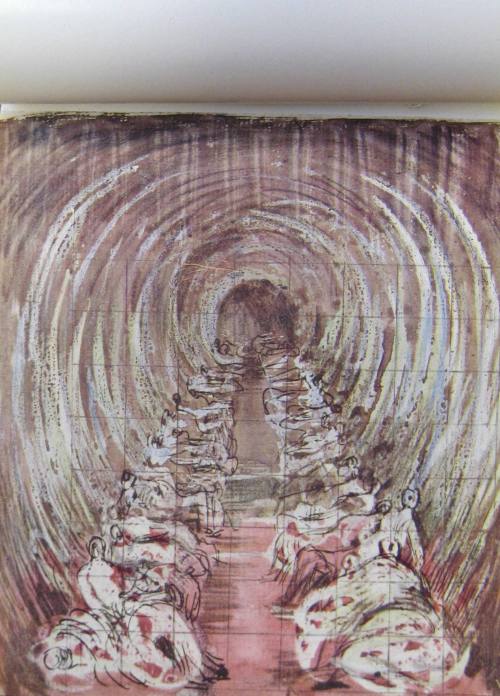

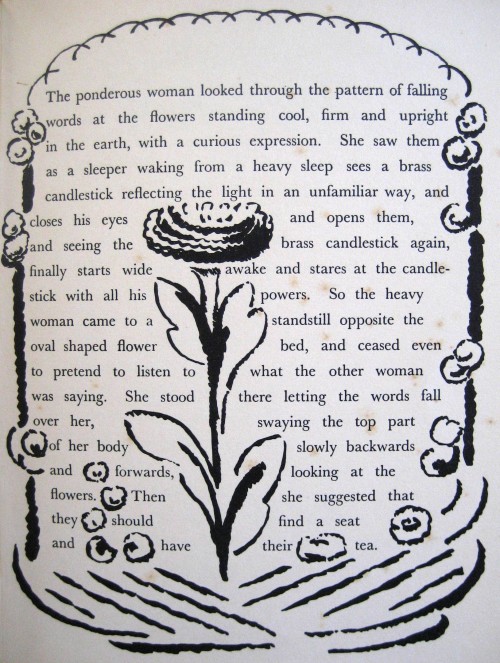

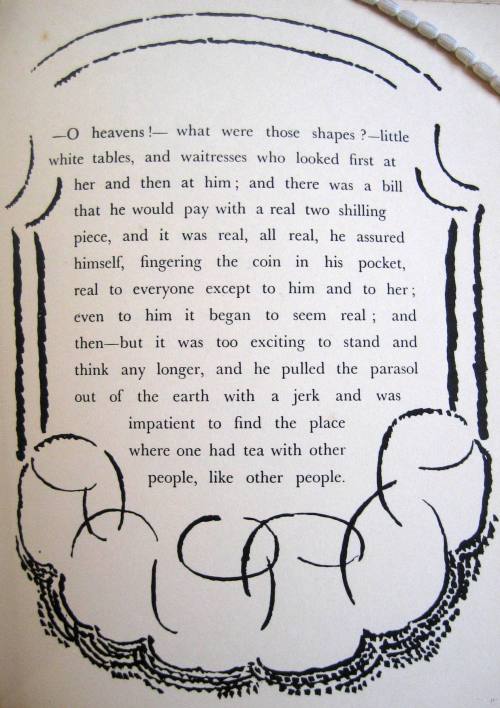

This approach is reflected in the 1927 edition of Kew Gardens illustrated by Bell and written by her sister. The margins of each page are decorated with strong black line motifs which do not directly portray the action on each page but do interact with the ideas in the text. On many pages there is a literal interaction between the words and the pictures which in some cases seem to fight for precedence. Sometimes the pictures win. On the other hand, Woolf’s text uses the vocabulary of the visual arts, words describing colour, shape and texture.

On this page the illustrations grow up into the text, pushing it out of the way. Kew Gardens by Virginia Woolf, with illustrations by Vanessa Bell. London : Hogarth Press. 1927.

The original 1919 edition of Kew Gardens was an early collaboration between the sisters. Bell provided drawings for the beginning and end of the text but she was not happy with the quality of the Hogarth Press’ production. She threatened not to illustrate any more of Woolf’s work if it did not improve. For the 1927 edition Woolf hired an external printer.

One of the more literal illustrations in Kew Gardens by Virginia Woolf, with illustrations by Vanessa Bell. London : Hogarth Press. 1927.

If you would like to find out more about Virginia Woolf in the Library browse in class mark YIK/WOO. For the Yeats family go to class mark YIK/YEA.

Other sources used in this post were:Bowe, Nicola Gordon. “Yeats, Susan Mary [Lily] (1866–1949).” In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Ed. Lawrence Goldman. OUP : Oxford. Accessed 30 Nov. 2012 <http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/61425>

Gillespie, D. F. The Sisters’ Arts: the writing and painting of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell. Syracuse University Press : Syracuse, N.Y. 1988. [YIK/WOO,G]

Lee, H. Virginia Woolf. Vintage : London. 1997. [YIK/WOO,L]

Lewis, Gifford. The Yeats Sisters and the Cuala. Irish Academic Press : Dublin. 1994. [YIK/YEA,L]

All images on this page are copyright of University College.

This post is for the curator’s inspiring sister, Mary Herbert.