Paul Bowles and Erich Alport

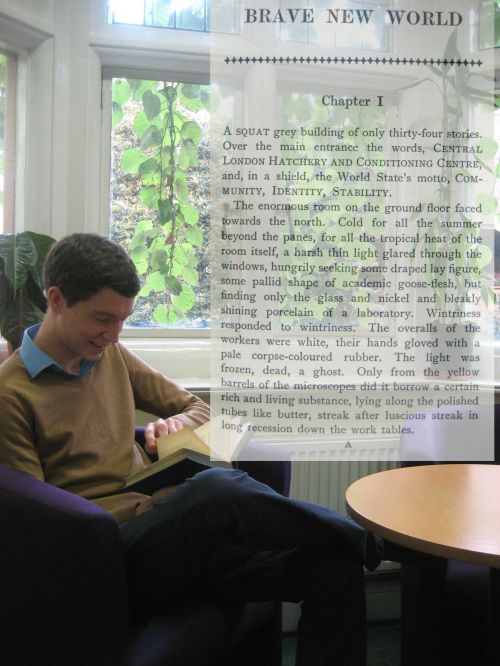

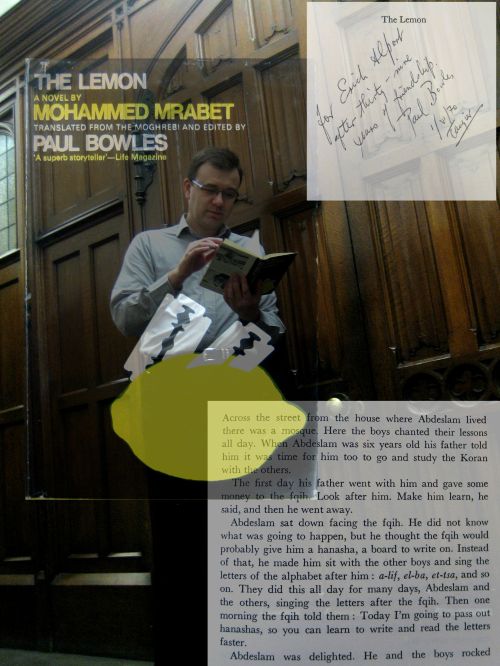

Rob, from the Univ Development Office, reading The Lemon by Mohammed Mrabet ; translated from the Moghrebi and edited by Paul Bowles. London : Peter Owen. 1969

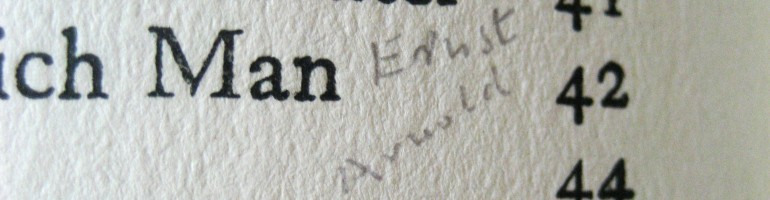

“For Erich Alport after thirty-nine years of friendship,” wrote Paul Bowles in the last book he gave to Erich Alport just a year before Alport’s death in 1971. Their long friendship is reflected in Alport’s ownership of first editions of nine of Paul Bowles works: novels, short stories and translations.

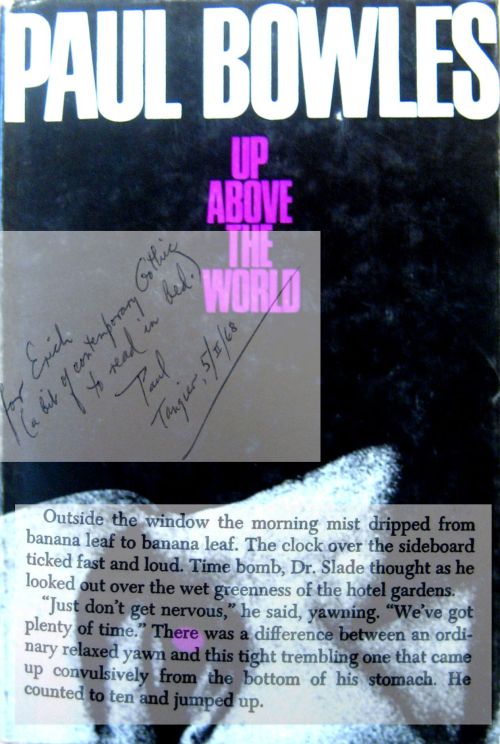

Cover and extract from Up Above the World. London : Peter Owen. 1967. Inside Bowles wrote, “For Erich (a bit of contemporary Gothic to read in bed.) Paul, Tangier, 5/II/68”. Excerpt from ‘Up Above the World’ by Paul Bowles. Copyright

1967, Paul Bowles. This is used with permission of the Paul Bowles Estate. Not for reuse.

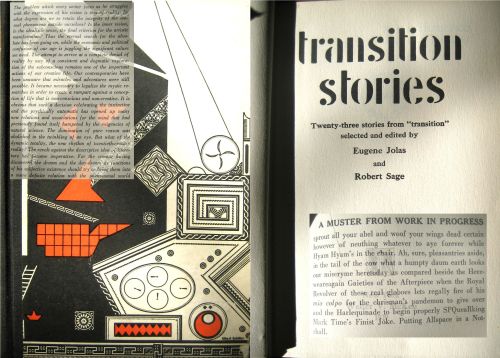

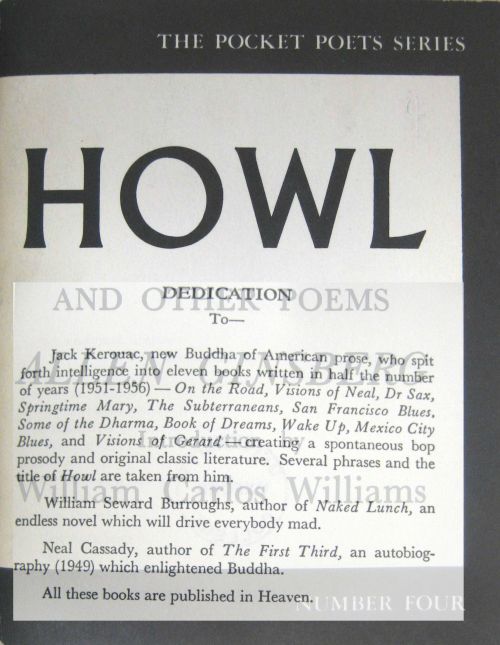

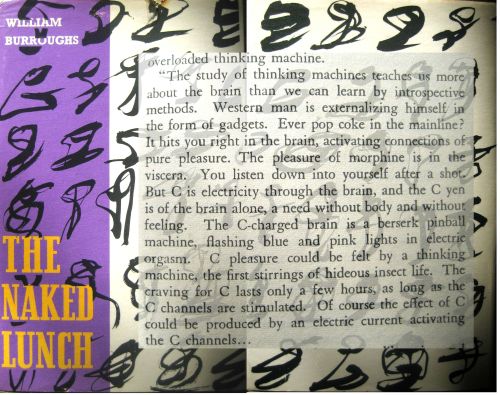

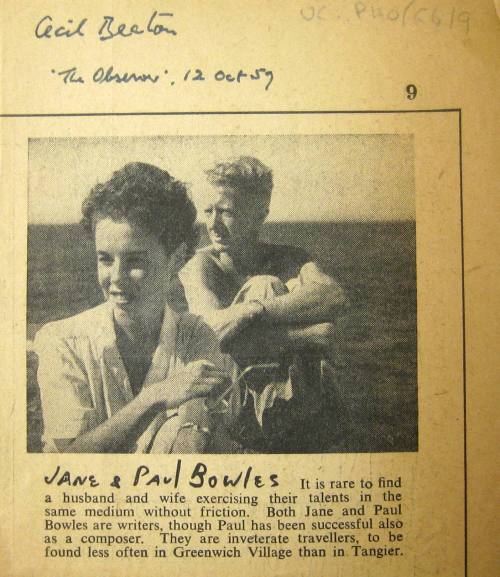

Paul Bowles started writing young. His poem ‘Spire Song’ appeared in the Parisian, Avant-Garde literary journal Transition when he was 17. Born in New York, he later made his base in Morocco and travelled widely. He was a prolific musical composer, collaborating in the theatre with Tennessee Williams among others. He increasingly turned towards writing and inspired authors of the American Beat Movement including William S. Burroughs. Jane Bowles, nee Auer, with whom he shared an unconventional marriage, was also an innovative writer.

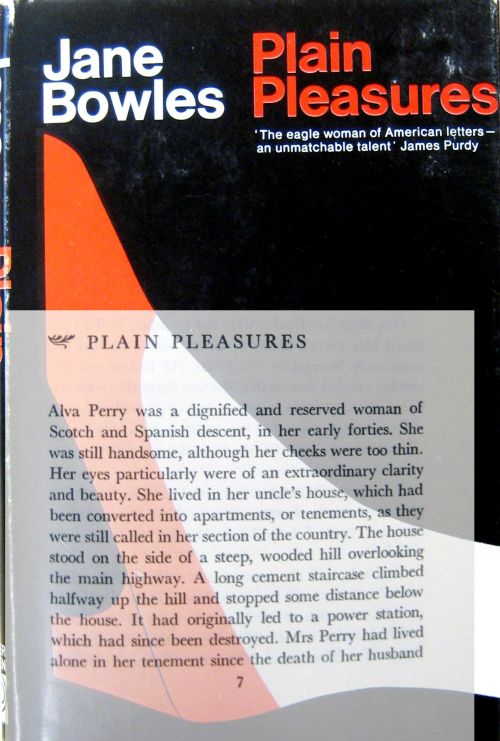

Cover and extract from Jane Bowles’ Plain Pleasures. London : Peter Owen. 1966. Excerpt from ‘Plain Pleasures’ by Jane Bowles. Copyright 1966, Jane Bowles. This is used with permission of Rodrigo Rey Rosa. Not for reuse.

Cutting from The Observer, 12 October 1959. It is kept in the University College Archives [UC:P110/C6/9].

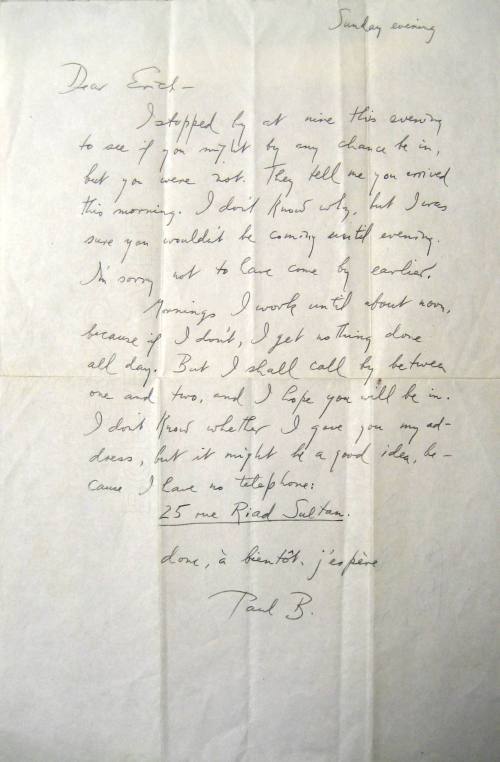

Letter from Bowles to Alport. It is undated but probably from the 1950s as it was found with other letters of that date in Alport’s copy of Bowles’ novel, The Sheltering Sky. It is kept in the University College Archives [UC:P110/C6/3]. Materials from the Paul Bowles archive. Copyright 2012, Paul Bowles. This is used with permission of the Paul Bowles Estate. Not for reuse.

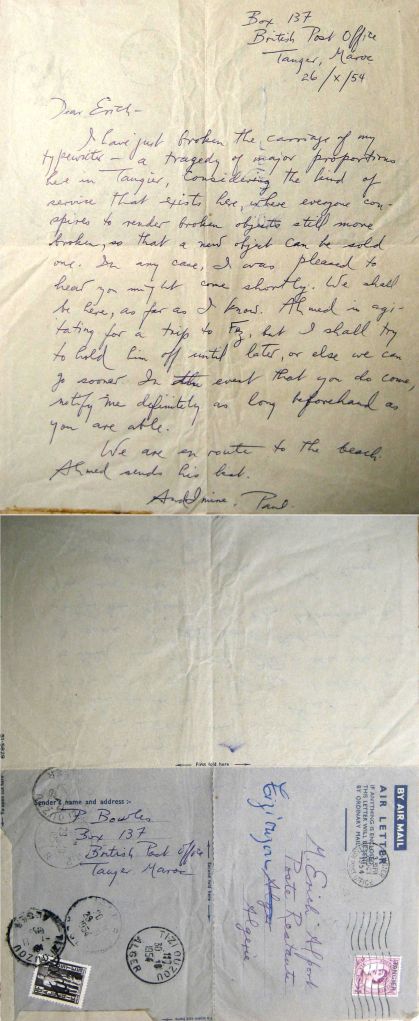

Letter from Bowles to Alport dated 26 October 1954. It is kept in the University College Archives [UC:P110/C6/4]. Materials from the Paul Bowles archive. Copyright 2012, Paul Bowles. This is used with permission of the Paul Bowles Estate. Not for reuse.

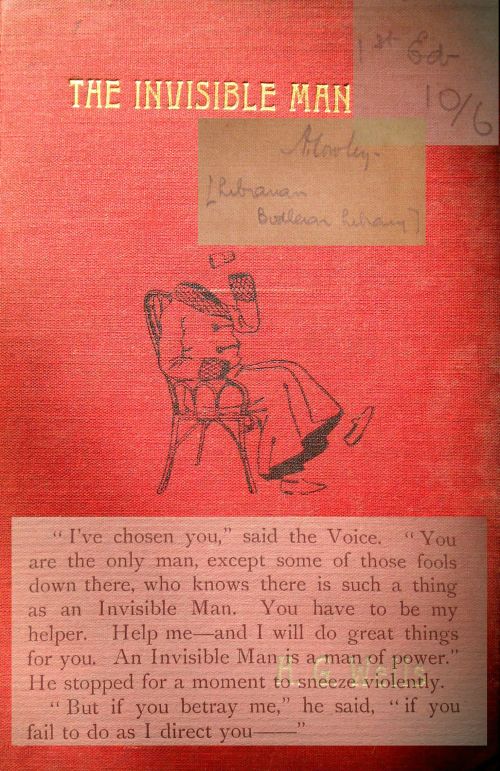

Paul Bowles and Gertrude Stein

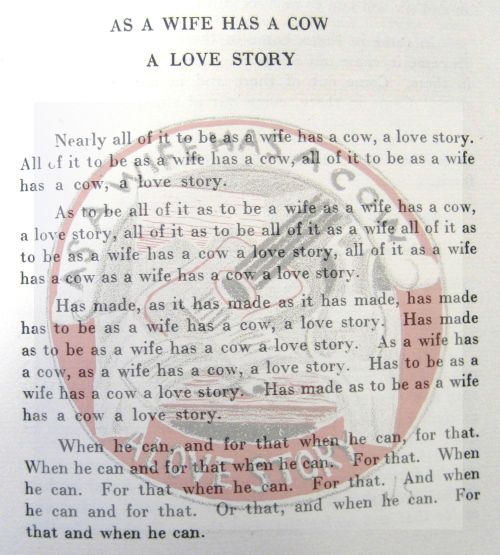

Paul Bowles knew of Gertrude Stein from childhood. In an interview with Florian Vetsch he recalls that in High School his English teacher told his class that they must write properly as they were not James Joyce or Gertrude Stein. This made him wonder who Gertrude Stein might be and led him to her ‘A Wife Has A Cow’ in a second hand copy of Transition magazine. He read it and thought it made no sense. Then he thought, “That’s wonderful. There [in Paris] you can publish things that don’t make sense at all and not even in proper English”.

Extract and illustration from A Book Concluding With As A Wife Has A Cow A Love Story by Gertrude Stein with artwork by Juan Gris. Paris : Editions De La Galerie Simon. 1926.

At twenty Bowles made his second trip to Paris and met Gertrude Stein in person (he didn’t meet anyone on the first visit as he was too shy). This and subsequent interactions with Stein had a great impact on Bowles’ literary career. It was she who suggested that he go to Morocco, a place which was to inspire him.

Bowles was among the young male friends Stein made after WWI with whom she had sexual as well as artistic nonconformity in common. Others included Virgil Thomson, Bernard Faÿ, and Francis Rose. The National Portrait Gallery at the Smithsonian has an excellent exhibition of images of Stein which includes more on these friendships.

Gertrude Stein in the Alport Collection

…the creator of the new composition in the arts is an outlaw until he is a classic – Gertrude Stein (Composition as Explanation, 1926)

Biographically speaking, Erich Alport overlapped with Gertrude Stein. Both were from German Jewish backgrounds, both were gay, both collected contemporary art. Perhaps this explains why Alport acquired several of her books. They also had acquaintances, such as Paul Bowles, in common. So perhaps Stein’s work was recommended to Alport by his friends.

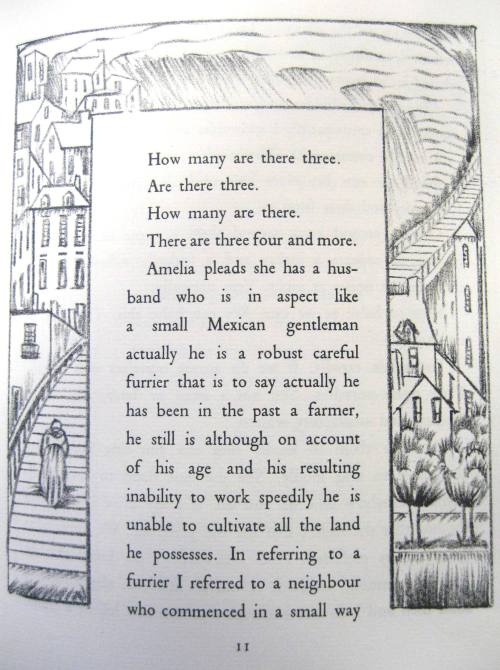

Page from A Village Are You Ready Yet Not Ready. Paris : Editions de la Galerie Simon. 1926. Alport’s copy is 31/100. The lithographs are by Elie Lascaux.

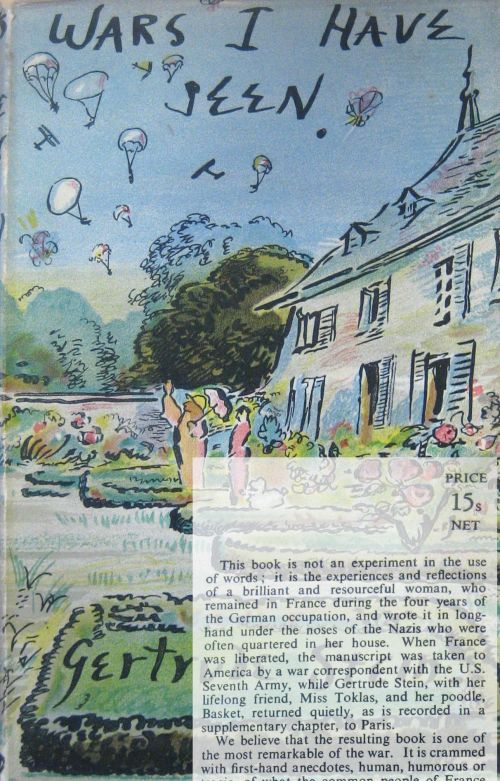

Stein’s work in the Alport Collection includes her experiments with language such as A Book Concluding With As A Wife Has A Cow and A Village Are You Ready Yet Not Yet, both published by Andre Simon in signed, limited editions of c. 100 copies. It also encompasses her bestselling books about herself, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, written by Stein from the point of view of Alice her life companion, and Wars I Have Seen, about her experience of living in occupied France.

Cover and publisher’s ‘blurb’ from Wars I Have Seen. London : B. T. Batsford. 1945. The cover design is by Cecil Beaton who was better known for his society photographs.

In Composition as Explanation, published in 1926 by Virginia and Leonard Woolf at the Hogarth Press, Stein talks about her writing. She touches on the effect of the World War on the reception of literature.

Cover of Composition as Explanation. London : Hogarth Press. 1926. The cover design is by Vanessa Bell, sister of the printers.

Stein posits that War broke the trend that art needs time to become socially acceptable (“classic”). War “made every one not only contemporary in act not only comtemporary in thought but comtemporary in self-consciousness made every one contemporary with the modern composition” (Composition as Explanation, p. 26). The literary world that Alport and his friends inhabited was one where those “who created the expression of the modern composition were to be recognised before we were even dead some of us quite a long time before we were dead” (Composition as Explanation, p. 26).

You can borrow some of Paul Bowles work from the Library:

The Sheltering Sky (YLM/BOW)

Collected Stories (YLM/BOW)

Other sources used in this post were:

Birch, Dinah (Ed.). The Oxford Companion to English Literature. OUP : Oxford. 2009. (ZC)

The Authorised Paul Bowles Website. Accessed 21 Nov. 2012 http://www.paulbowles.org

Seeing Gertrude Stein: Five Stories. Online exhibition from National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Accessed 21 Nov. 2012 http://www.npg.si.edu/exhibit/stein/intro.html

All images on this page are copyright of University College.