Henry Moore’s drawings

Henry Moore was primarily a sculptor as defined by Herbert Read:

The complete sculptor…will be prepared to use every degree in the scale of solids, from clay to obsidian, from wood to steel – Herbert Read (Introduction to Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, 1944)

Drawing, however, was integral to Moore’s artistic practice throughout his career, albeit with a changing relationship to his sculpture over the years. Drawings feature in all the books about Moore in the Alport Collection. Alport also owned at least one of Moore’s sketches.

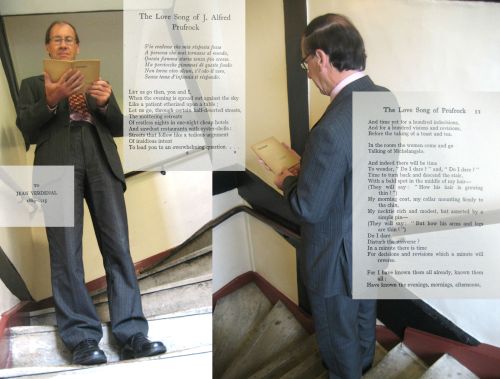

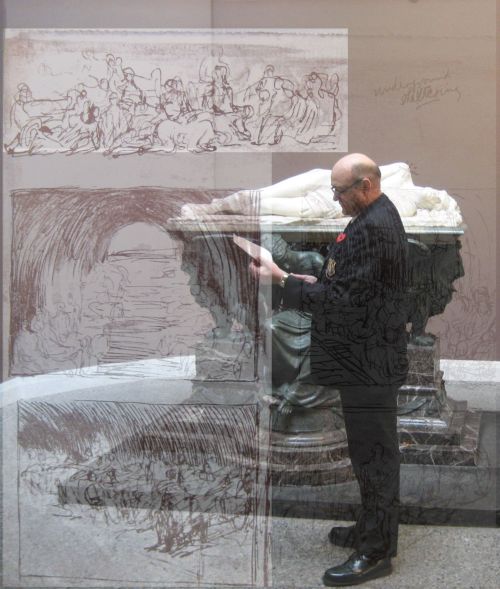

Colin, one of Univ’s Porters, looking at Shelter Sketch Book by Henry Moore. Editions Poetry London : London. 1940. Colin is standing beside one of the sculptures to be found around the College, The Shelley Memorial. It was created by Edward Onslow Ford in the late nineteenth century.

Early work

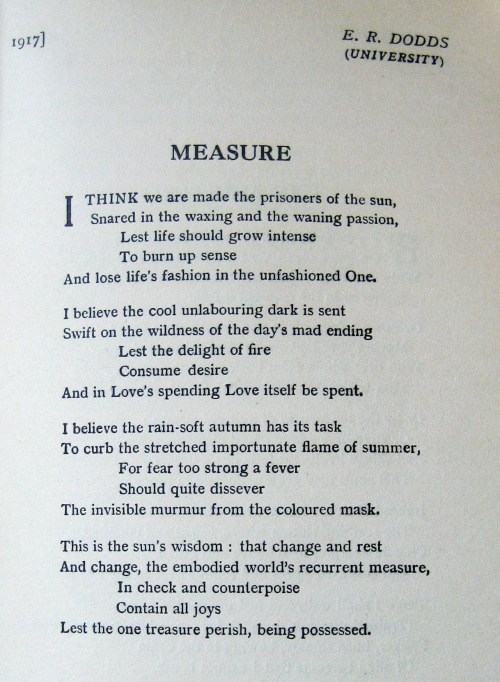

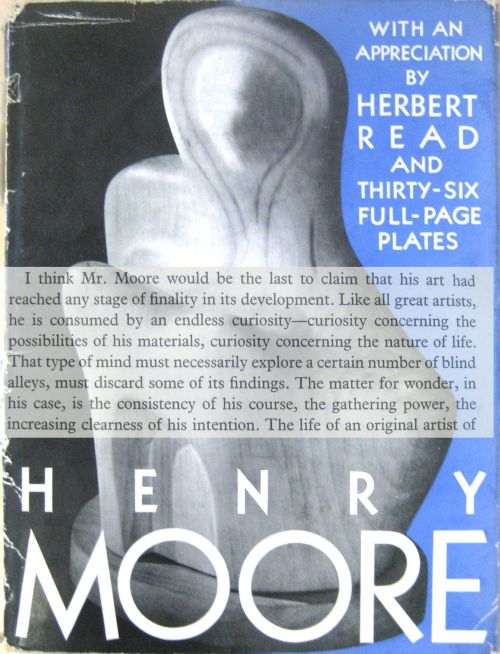

The first book dedicated to the work of Henry Moore was published in 1934 at a relatively early stage in his career (he attended art school after serving in WWI). In his introduction Herbert Read praises Moore unreservedly as at “the fullness of his powers” and offering “the perfected product of his genius”.

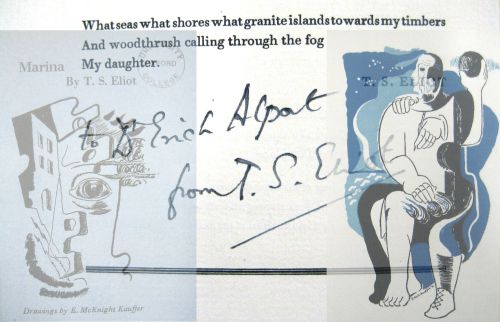

The cover of Henry Moore. A. Zwemmer : London. 1934, with part of Herbert Read’s introduction (p.16)

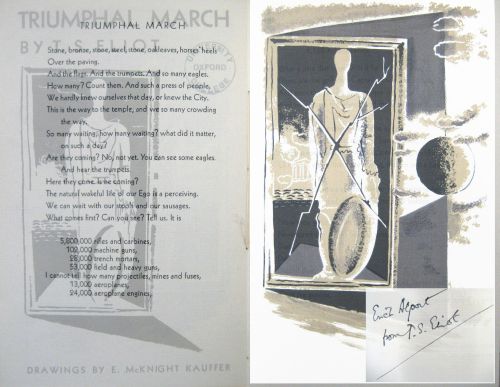

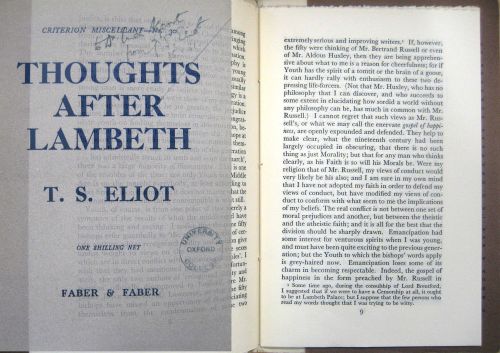

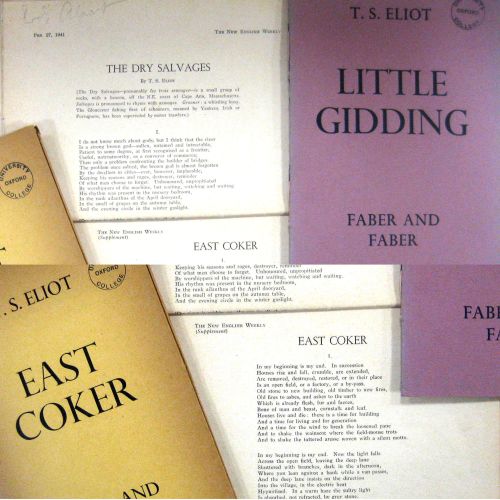

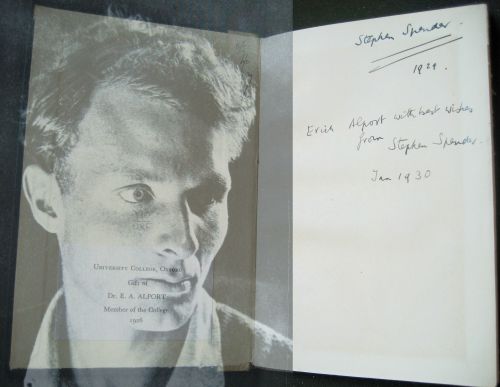

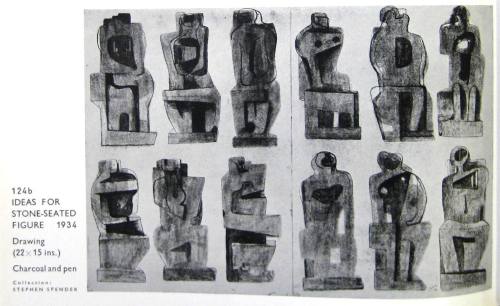

Between the wars, Moore lived in Hampstead. He had friends nearby among whom were other artists such as Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson; architects like Walter Gropius; and writers including Alport’s acquaintances, T.S. Eliot and Stephen Spender. Stephen Spender also collected work by Moore. The picture below, from Stephen Spender’s collection, exemplifies Moore’s use of drawing to inspire sculpture at this stage in his career.

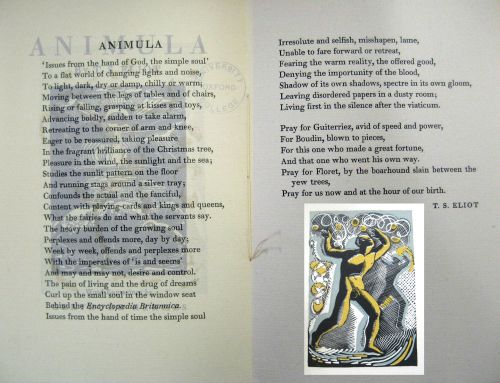

Ideas for Stone-Seated Figure, 1934, 22 x 15 ins., charcoal and pen, from the collection of Stephen Spender, featured in Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings. London : Lund Humphries and Company. 1944.

Shelter Sketch Book

It is the human figure which interests me most deeply – Henry Moore (‘Notes on Sculpture’ in Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, 1944)

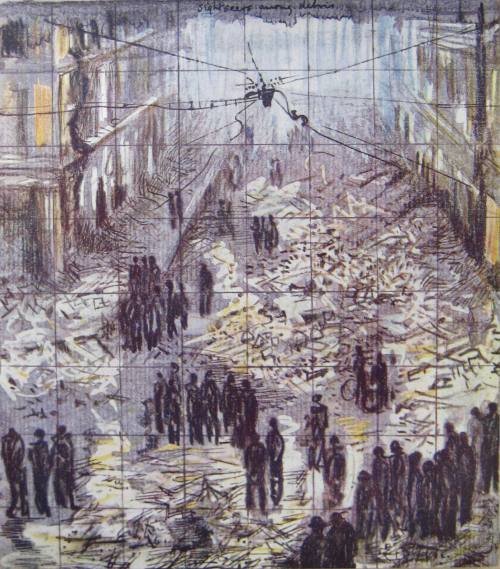

The outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 brought a halt to Moore’s production of sculpture. As the War progressed the materials he needed became harder to obtain and he made no sculptures between September 1940 and June 1942.

Moore continued to draw during the War and, as Herbert Read wrote, his output during this time allowed “a far larger number of people…to enjoy and possess some example of the artist’s work than would otherwise have been the case” (Introduction to Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, 1944).

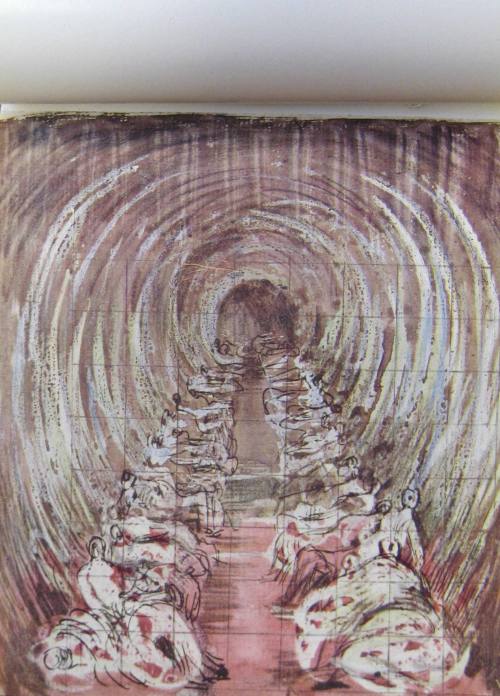

One night in September 1940, Moore and his wife had to stay on the platform at Belsize Park underground station during a bombing raid. Moore was fascinated by the figures of the Londoners, men, women, and children who were spending the night there sheltering from the Blitz. Within a few days he produced the first of his shelter drawings.

Moore’s shelter drawings of 1940–41 were exhibited at The National Gallery during the War. They transformed Moore’s public reputation. He went almost overnight from an avant-garde artist to one whose work Londoners could identify with.

Festival of Britain

In 1951, Moore was commissioned to produce a sculpture for the Festival of Britain (organised by the government to promote a sense of recovery after WWII and to celebrate British achievements in the arts, science and technology). The outcome was the bronze Reclining Figure: Festival, a cast of which is now held at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh. The Arts Council also arranged Moore’s first London retrospective, at the Tate Gallery, to coincide with the Festival.

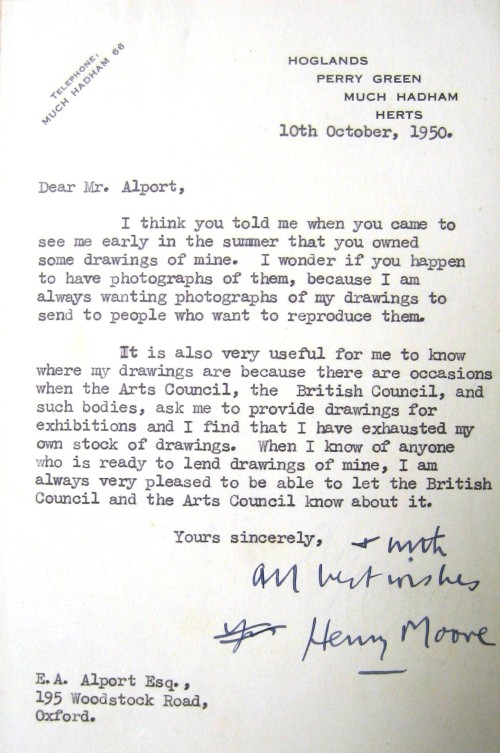

The year before this exhibition Alport went to see Moore at his studios in Perry Green, Hertfordshire. His visit prompted Moore to write asking for photographs of the examples of his drawings in Alport’s collection. Moore also mentioned that the Arts Council might be interested in borrowing the works for future exhibitions.

Letter from Henry Moore to Alport written on 10 October 1950. It is kept in the University College Archives [UC:P110/C24/1].

Letter from Henry Moore to Alport written on 15 January 1951. It is kept in the University College Archives [UC:P110/C24/2].

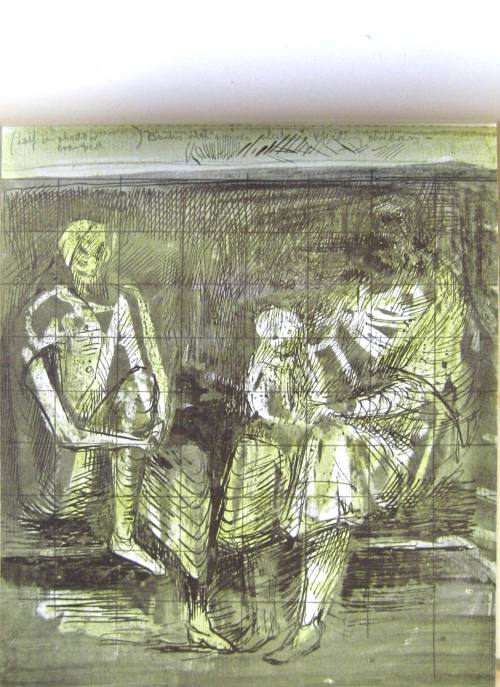

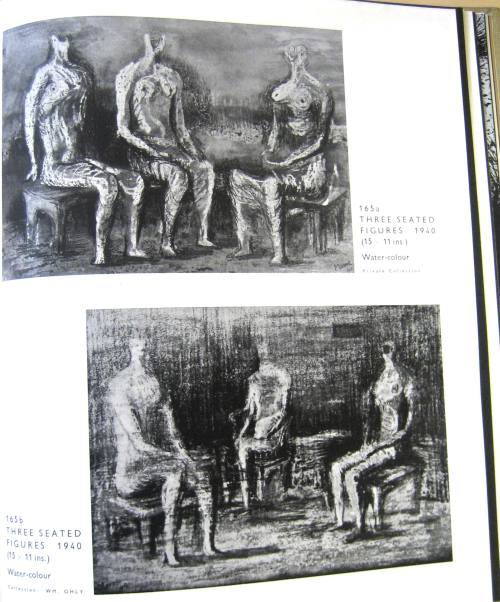

Drawings of three seated figures featured in Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings. London : Lund Humphries and Company. 1944.

Later drawing

By the mid-1950s Moore’s drawings were no longer his means of generating ideas for sculpture. Instead he took inspiration from natural forms such as bones, shells and stone, from which his sculptural ideas evolved.

Moore returned to drawing when he took up print making later in life. By then drawing, for him, was a separate activity from sculpture. From 1970 he produced an great number of drawings, particularly during the early 1980s when he was too ill to work on his sculpture. Many of his drawings are exhibited alongside his sculptures at his former house and studios in Perry Green, Hertfordshire, which are now the home of the Henry Moore Foundation. They are well worth a visit.

Other sources used in this post were:

‘Henry, OM, CH Moore – 1898-1986’. Accessed 5 Nov. 2012 at http://www.artfact.com/auction-lot/henry-moo-5xy5t6owvf-13-m-ec6de58c4c

Wilkinson, Alan. “Moore, Henry Spencer (1898–1986).” in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. OUP : Oxford. Accessed 5 Nov. 2012 <http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/39962>

All images on this page are copyright of University College.